When You're Too Sad To Write

It feels peculiar to have months too tender to write from now.

Time was, I traveled across half of the continental U.S. with a Ford Explorer as my only home and the post traumatic stress levels of a soldier returning from war—writing through every muted, confusing discomfort my nervous system could manufacture. Every nauseating tremor of my high-alert brain was assigned some blurb of clever commentary, usually posted to social media.

During that era, I would walk roughly 6 miles every morning, writing poetry in my notes app the whole way.

That would be fairly uncomfortable to do now. Today, I prefer to take in the scenery—both inner and outer—on my walks, then return to a stationary laptop to write. Back then, though, these long, narrated walks were regulating my constantly strained nervous system.

That system was constantly in a low-grade state of fight or flight, had a mountain of buried trauma frozen in its fascia, and ran hot on internalized self-hatred it never chose.

No wonder I was oblivious to the concept of letting a moment breathe. You have to love yourself to start taking emotionally skillful considerations like that.

Until I began unpacking my trauma, I subconsciously believed that incessantly describing my negative feelings would somehow let me bypass the hard part of feeling them.

You could honestly sum my entire adult life up as a series of misguided attempts to dodge that hard part of confronting my emotions directly—each attempt making things worse—followed by a final surrender to the reality that it’s my shit to shovel, so I might as well get to digging.

And if I could say anything to other folks traumatized in childhood here it would be: don’t be like I was. Don’t get yourself tripped up on how unfair it is.

Of course it’s unfair. Grown ass people mismanaged the wiring of your wee child brain so badly that you have to do a repair job as an adult—one that costs an amount of time, money and energy it would be depressing to calculate. Be that as it may, healing from trauma is about bettering your quality of life, not excusing the people who wounded you, so put that spade to soil.

I’m in the trenches now. In the shit, as they say.

A perk of doing all this trauma work, as unpleasant as it can be, is that when I’m going through a period of particularly deep and discomforting emotional upheaval, I can just go through it. I don’t have to chase after a thousand ways to suppress it. I don’t need to invent a story to explain it if I don’t know why it’s happening. I’m not obliged to turn my feelings into content before I’ve even felt them.

I no longer have to meme the madness. I can just cut straight to observing the anguish.

Anything creative I might later produce about it will serve me, not the other way around.

After you’ve done the work for a while, you start to lose your fear of sadness because you realize what you were afraid of wasn’t actually sadness.

In the frozen, corroded world of trauma, what you fear is a grotesque snapshot of sadness deferred: an emotional debt lodged in your mind like a festering splinter—both dead and alive in all places you don’t want it to be. A wound stuck in time impervious to all misguided attempts to drink, drug, fuck, gamble, shop, joke, charm, or succeed it away is genuinely terrifying.

Why wouldn’t it be?

The abuse and neglect that caused my C-PTSD started so young that I assumed all despair operates like that, as this glutinous mass of caustic slop that threatens to swallow you whole like the melting mirror in The Matrix if you so much as jab it with a fingertip.

So I ran.

And ran, and ran for decades until I couldn’t bear the weight of taking another step—except the one to turn and face my trauma.

When the inner Siberian tundra of unprocessed trauma starts to thaw under the light of your awareness, you realize something surprising: even the most devastating emotions transform under observation.

True observation. Not intellectual dissection, but present-moment witnessing.

It turns out that the monster you fled from fed off of your frantic footfall. When you turn around and give it a proper look, you see it’s not a monster at all.

It’s a child. And the child is hurt. And the child is you.

Before that shift in understanding, if I fist-fought a tweaker I would be writing about it before the adrenaline wore off enough for me to feel my hands.

Before the work, I leaned heavily on my outward identity as a writer, memer, online provocateur, what have you. There was this implicit sense that my own life was slipping through my fingers, and if I didn’t capture it, I would forget, and if I forgot, then I would never be able to convince people of my worth by way of my wit and storytelling ability.

During the work, I realized I was so preoccupied with my perceived place in the world because I had no self-worth reassuring me that I didn’t have to demonstrate a right to exist. Once my self-worth bloomed, it was clear that I had one just by virtue of being alive.

I still care about my place in the world after the work, too, the sensation has just lost its teeth. It is no longer so urgent I do everything in my power to avoid dying in obscurity.

I’d like not to, but I refuse to hate myself across the finish line.

I honestly feel sorry for people who do. I know how that self-hatred works inside and out because it once made a home in my bones. You could get out there and win the EGOT, and that shit will convince you that you did it wrong.

Another thing that became clear during the work was just how little I’d allowed myself to feel.

I learned repression so early in life that before the work, I cannot remember treating a negative emotion that might inconvenience others as anything other than radioactive waste to be quickly and quietly disposed of.

And by “disposed of” I mean stored in a clandestine warehouse indefinitely, because all stifled sorrows have a half-life as long as uranium-235.

Let me crack open a barrel and serve you a radioactive dram of misery juice from the Y2K era:

So, I go to a psychiatrist for depression in my mid teens and he talks to me for all of 15 minutes. During that 15 minutes he determines I need a prescription for Paxil—I didn’t—and tries to convince me that I’m libertarian.

I was too young and ignorant to know the last part was crossing a weird line until years later.

I left that office thinking I probably was libertarian—I wasn’t—with a grand total of zero constructive solutions for being sad all the time. I say all this to communicate that looking back, I find it at best unhelpful, and at worst some mild form of medical malpractice, that I never got a question like, “how’s your home or school life?” When being assessed for any kind of mood disorder.

That my father’s father was a physically, verbally and emotionally abusive alcoholic and he never received a minute of therapy for it seems unbelievably relevant in retrospect, but I digress.

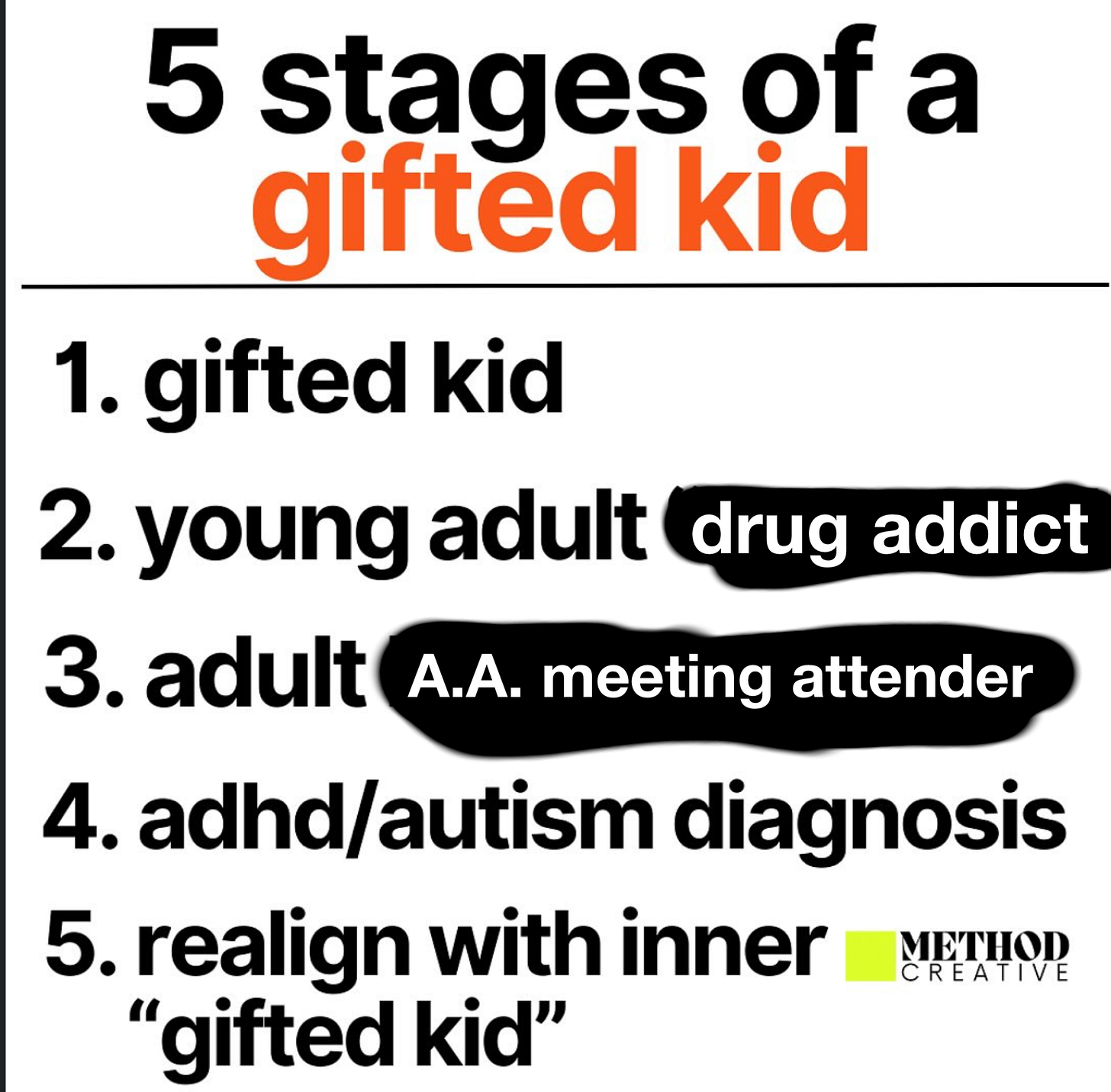

Once I made an incision into my unprocessed emotional rot and started draining the wound, I found there was a certain rhythm to it. I sometimes wonder if one’s subconscious knows exactly how much grief you can take at any given moment, and modulates this rhythm based on that data. However it works, what the rhythm looks like in practice is my psyche unfreezing blocks of trauma in waves.

You can tell God loves a wave. They’re everywhere. On the physical level, the emotional level, the quantum level. Divinity is such a geek for a valley and a peak. You take an ebb, you take a flow, you put them together and what have you got? The gesticulation of the conductor of the universe, to be sure.

About a month ago, the Maestro indicated it was time for my soul to scream in C minor, so a tsunami-sized wave hit me in early December and I’ve been enduring a somatic crying session just about every day since.

This wave isn’t fully over yet, but I’ve found enough of my bearings within it that I feel ready to articulate myself about the experience.

I could have articulated myself about it earlier, but it would’ve caused more emotional strain than I had space on my plate for, so I waited. That’s the difference between an artist creating because they want to create, and an artist creating because they need their own work to vouch for them.

Let me offer my own former writing process by way of contrast.

The plot of my first novel is simply recounting the first year I started doing trauma work, and when I was writing it, I didn’t understand a single thing I’m explaining to you now.

I was writing poetry to cope during the dark night of the soul that popped the cork of my unprocessed trauma, and before I knew it, I had an embryo of a collection I wanted to share. As the collection grew, so did my intuitive sense of what the novel was about. I essentially realized I was writing the novel as I was living it.

Once that clicked, I became overeager to commit anything remotely interesting about my life to the page. Whether it was excruciating or outright unproductive to write about traumatic or astonishing experiences before I’d integrated them just did not occur to me.

For one thing, I’d learned just enough about trauma release to know that writing mattered, so I assumed any writing about long‑avoided material had to be healing-adjacent.

For another, and more pertinently, I’d only ever regarded my own comfort in a way that was maladaptive.

I only sought comfort externally through drugs, sex and distraction, because the notion that I could self-generate comfort felt absurd. I never checked in on my interior world like you would a friend and asked, “Hey man, how’s it been going?” the way I do now.

When you take all the extrinsic behavior away, but you haven’t learned the intrinsic behavior that is meant to replace it yet, the gap in knowledge can cause a bit of calamity.

While penning that manuscript, I wrote about an acid trip while ascending its peak and walking shirtless down Sunset Avenue.

I wrote about somatic crying sessions I’d barely finished with tears still in my eyes.

I wrote about ketamine treatments while descending into k-holes until language no longer made sense. Just in case I caught something vital, you know?

And most importantly, I wrote about traumatic events before I was ready and risked retraumatizing myself several times.

I was just jumping face-first into the void and having a swim because I’m impulsive, too cocksure for my own good, and I once channeled those qualities into a frantic search for proof I was worth something. Finally having something substantial to write about was exhilarating, even as I bore more formerly pent-up grief than I ever had in my life.

I hadn’t worked through enough trauma to recognize that trying to validate my existence with a novel about working through my trauma was itself a trauma response.

To be fair to me, that is a nontrivial riddle to unravel, and I wouldn’t fault anyone for taking however long it took to figure it out if they were in my shoes.

The fact I’ve never been especially good with moderation didn’t help matters.

When I did drugs to run from pain, I did heroin. When, at long last, I decided to ditch a behavior as primary as running from pain, I slammed on the brakes with no forethought as to what I might do when I was thrown from the car and thrashed across that black sea of sorrow like a rag doll without so much as a counselor to tap in with.

That sort of recklessness was a form of self-abandonment. It was a footstep towards self-acceptance, made only in the way someone who hates themselves can make it, paradoxically enough.

There’s a certain protective numbing that happens when people become traumatized; I think culture at large mostly understands that much. When those same people fundamentally reverse engineer their pre-trauma brain configuration—or build a regulated system from scratch if the trauma happened young enough—through any effective trauma therapy, that numbing wanes.

That part gets less media coverage. As a result, I think people vaguely know that healing from trauma is “good,” but have little sense of how difficult it is for a defrosting trauma brain to grapple with regaining sensation. It might not know what is causing feeling, not right away, but the fact it is having a feeling and what that feeling is are both agonizingly clear.

At first, doing the work feels like getting into a hot shower after playing in the snow.

The parts of you that were numb go through a phase where positive stimulation feels like pain.

Every time I showed up for myself, it made me want to cry. Every self-directed “I love you” felt like a knife to the heart. And recovering interoceptive cognition felt like having been deaf, getting an implant, and struggling to acclimate to sound.

Eventually, though, your awareness of your emotional landscape becomes just another sense.

Periods of intense grief become just that. Pain is no longer an identity. Even when its persistent, it’s never pernicious. It’s just a bad storm passing through.

Beyond that, every bad storm nudges the tundra that much closer to becoming a forest.

I could write about my specific insights into how I’ve been abused, neglected and let down, and by whom, but I find them secondary. Nearly unnecessary, honestly. Handy, yes, but ancillary at best.

When you’ve never had a moment of peace in your life and you start to put a few together, who did what only matters insofar as you knowing what mistreatment you’ll no longer tolerate from people.

That’s extremely useful, but the peace is the prize.

And it’s not even close.